A Dust-laden Collaboration

A Story AboutRichard Strauss and Stefen Zweig

Onthe night of November 9, 1936, when Carl Goerdeler, the Leipzig's moderateconservative mayor, was briefly out of the country, his second-in-command, aNazi loyalist named Rudolf Haake, saw his opportunity: the enormous Leipzigstatue of Felix Mendelssohn was demolished and removed, while details of itsdestruction have not yet come to light, the likeliest fate for all reclaimedbronze was the German armaments industry, which became desperate for rawmaterial. And so it is eminently possible that this Mendelssohn memorial of1892 - unveiled within the living memory of many Leipzigers, and laterdescribed by the conductor Fritz Busch as an homage to the entire "spiritof German culture" - ended up as casing for bullets.

Whilea statue could be ambushed in the middle of the night, the memory ofMendelssohn's legacy in German music would prove more difficult to erase. TheGerman public adored some of Mendelssohn's most celebrated scores, includingmost of all his Midsummer Night's Dream Overture. It was therefore determinedthat a suitable replacement by a racially acceptable composer would simply needto be created. To his credit, Richard Strauss demurred. The composer Carl Orffand forty-three other composers tried their hands, none of them produced aversion that ultimately gained acceptance, so in the end the Nazis resorted toplan B: Mendelssohn's beloved Shakespeare music would continue to be performedwith his name simply eliminated from the program.

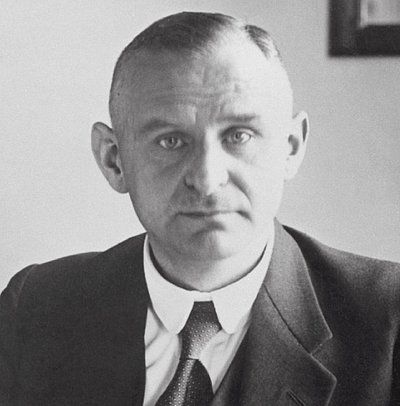

RichardStrauss would surely have opposed the removal of the Mendelssohn statue, justas he had declined to replace Mendelssohn's Shakespeare music with his own; hehad Jews among his own family, and moreover, his understanding of the art'shistory was far too complete to sanction such gross distortions. But whenHitler first came to power, Strauss nonetheless profoundly misread the Nazithreat, seeing in the party's muscular approach to culture a new opportunity forshaping Germany's musical future according to his own vision. When the newregime offered him a position of power, Strauss chose to accept. Yet ratherinconveniently, the composer's self-serving early engagement with the NaziParty came at a sensitive moment in his own operatic career. Since the death in1929 of Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the gifted Austrian-Jewish poet and playwrightwho had served as the composer's librettist for more than two decades, Straussfeared in earnest that he would never write another opera. That is, until hewas introduced to a writer who seemed perfect for the task. In 1931, RichardStrauss met Stefan Zweig.

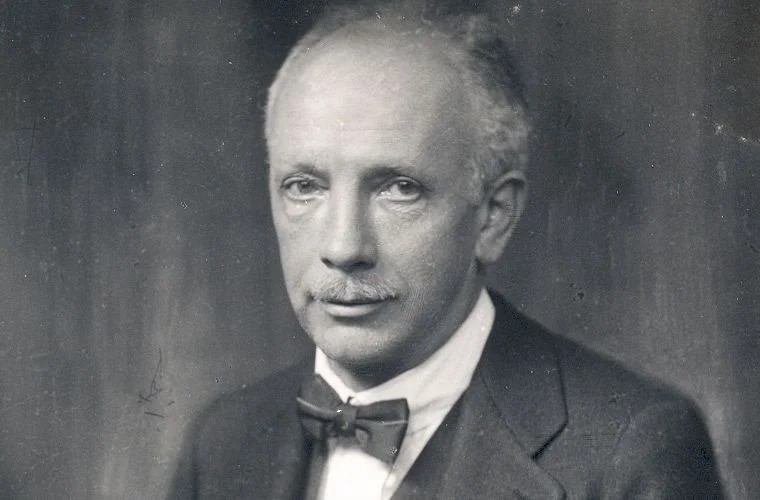

Zweigwas born in 1881 into a multilingual Jewish home of privilege, his motherhailing from a successful banking family and his father a music-lovingindustrialist who had once heard Lohengrin performed under Wagner's own baton.

As a writer, Zweig published fiction, plays, and poetry, but he specialized inbooks that explained for his readers the lives and works of the great artists,scientists, and explorers of the past: Balzac, Tolstoy, Erasmus, Montaigne,Magellan, and many more. Around the time of Strauss and Zweig's first meetingin 1931, Zweig had just turned fifty and was at the peak of his fame. As themost widely translated German writer in the world, Zweig was a bona fideliterary celebrity. A lecture he once gave on Tolstoy drew a crowd of fourthousand people. On a fall tour of two Swiss cities, he wrote home to his wifein a happy state of depletion, reporting, "I had to sign nearly eighthundred copies of my books in the two bookshops. ... I'm writing this letter onthe train, in pencil, because my fountain pens (all three) have run out."

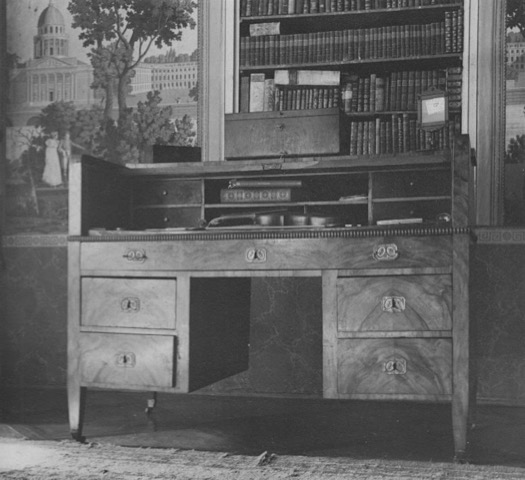

Zweig'sdevotion to his religion of humanism, in which art and culture counted as"our true homeland," manifested itself not only in his writings butalso in his ceaseless work as a collector of original manuscripts. He had aparticular love for music and purchased hundreds of manuscripts (many of themnow in the British Library) by the great composers including Bach, Brahms, andSchubert. Beyond musical manuscripts, Zweig also tracked down everyday objectsonce owned by the composers themselves, including Mozart's marriage contract,Beethoven's compass, violin, and cream spoon. He owned a fountain pen ofGoethe's and even a lock of his hair in addition to manuscripts in the poet'shand including a double leaf from part 2 of Faust. Yet Zweig's most treasuredobject, one that he kept with him until the last possible moment, wasBeethoven's desk. He used it as his own writing desk and referred to it as his"family shrine." The true collector does not give his prized objectsa second life, Walter Benjamin once wrote, but rather"it is he who livesin them."

Zweigwas thrilled at the prospect of a collaboration with Strauss in particular. Ashe later recalled, "There was no creative musician of our time whom Iwould more willingly have served than Richard Strauss, last of the great lineof German composers of genius running from Handel and Bach, by way of Beethovenand Brahms, and so to our own day." The two men got down to work quickly.At their very first meeting Strauss explained with surprising candor that athis advanced age he no longer possessed the same power to create ex nihilo thekinds of purely instrumental music that had marked earlier high points in hiscareer. Yet words could still inspire him, and he craved a truly poeticlibretto. Moreover, of all things, he hoped this new work could be a comicopera. Zweig soon suggested an adaptation of Ben Jonson's comedy of 1609 titledEpicoene; or, The Silent Woman, about an old bachelor named Morose (in Zweigsversion, Morosus) who is desperate for peace and quiet and is tricked intomarrying a "silent woman," only to find she is the very opposite.Strauss heartily embraced the idea, and work on their new opera, Dieschweigsame Frau, began at once.

Theirsurviving correspondence reveals just how quickly Die schweigsame Frau cametogether, as Zweig seemed to intuitively grasp what Strauss needed in order tospark his own musical imagination. In one early missive, Strauss pronouncesZweig's draft as possessing a greatness of historic proportions, "moresuitable for music than even Figaro and the Barber of Seville." Withartistic matters as the prime concern of their letters, contemporary politicalevents, for long stretches, remain almost surreally absent. On January 31,1933, for instance, Zweig writes to Strauss calmly and deferentially about thelogistics of an upcoming meeting, and does not even mention the dramaticdevelopment of the previous day: the swearing in of Adolf Hitler as thechancellor of Germany. Not until a letter of April 3 does Zweig's discretionallow for a vague reference to "these upsetting times" as havingdisturbed his own work. In responding to Zweig's letter the following day,Strauss could only shrug: "I am doing fine. Again I am busily at work,just as then, a week after the outbreak of the Great War." Zweig'ssubsequent reply strains to coolly echo this sentiment: "I am delightedthat your work proceeds well; politics pass, the arts live on, hence we shouldstrive for that which is permanent and leave propaganda to those who find itfulfilling and satisfying."

Theirreasons for keeping politics out of their correspondence were both similar anddifferent, by the 1930s, however, the spheres of both music and literature formen like Strauss and Zweig had become preserves of interiority, places ofrefuge for the spirit in a world grown loud and coarse.

Asthe Nazi campaign against German Jewry intensified in the early years of theThird Reich, Zweig recognized the situation clearly as an instance of thefloodgates opening, but he also tried to keep "a cool head," whichmeant attempting in his public statements to remain above the political fray.("There is nothing of the so-called heroic in me," he conceded in aletter to another correspondent, adding, "A secret feeling tells me thatwe act rightly if we remain true to humanity and renounce the temptation totake sides.").

Strausstook a very different view of the situation. "I made music under theKaiser and under Ebert," he wrote. "I'll survive under this one aswell." Yet he would succeed in mustering something more than wearyresignation toward the new regime as he quickly came to sense that the momentmight present an opportunity to advance the cause of German music, itself acorpus in which, as he saw it, his own operas naturally occupied a centralplace. Thus Strauss wrote in a letter of March 1933 to his friend (and Zweigspublisher) Anron Kippenberg, "I have returned with great impressions fromBerlin and am full of hope for the future of German art, once the first stormsof revolution have subsided."

Straussmay have also sensed a regime hungry for his approval in a way that politicalleaders of the interwar era had not been. Just as Strauss had bent the kaiserto his will, perhaps he might accomplish something similar in Germany's newestReich. Strauss's version of the Innerlichkeit tradition then, rather thandictating a principled Zweigian withdrawal from politics in toto, seemed toauthorize an ethically convenient if patently false separation betweenpolitical maneuvering and the creation of true art. Strauss appeared to feel nocompunction whatsoever about pursuing both simultaneously. And so while 1933marked a new level of political engagement for the composer, he saw no reasonwhy this should have any bearing on his new operatic partnership with hisprized Jewish librettist.

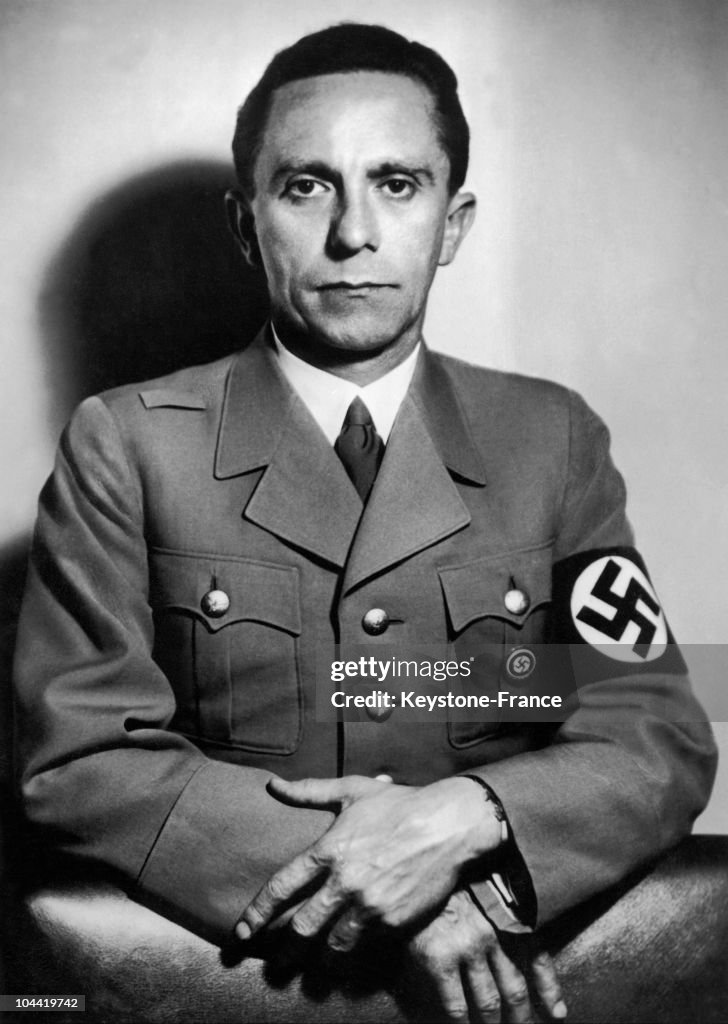

Meanwhile,Strauss wasted little time ingratiating himself with the regime through aseries of public gestures. In addition to substituting for Bruno Walter at theBerlin Philharmonic, he replaced Arturo Toscanini at the Bayreuth Festival,after the Italian conductor had withdrawn in protest against the new Reich. AsZweig himself later noted, Strauss's apparent approval was tremendouslyimportant at that early moment because it tacitly legitimized an insecuregovernment. Around this time, Strauss also curried favor with Goebbels and theNazi leader Hermann Göring and lent his name to an ideologically motivateddenunciation of Thomas Mann for a speech on Wagner that Mann had delivered atthe University of Munich. By November of that year, Strauss's efforts wererewarded. Whether he actively sought an appointment as president of the ReichChamber of Music or, as he later claimed, had this public role somehow thrustupon him, he zealously accepted his new assignment at the helm of a freshlyestablished organization tasked with shaping and administering the field ofGerman music. At its official opening, Strauss made a rousing speech, thankingHitler and Goebbels for creating the new Chamber of Music and pledging it wouldrestore the country's most exalted art form to its nineteenth-century glory.The organization's ultimate goal, he declared, would be "to once againestablish an intimate relationship between the German Volk and its music."As we know, what Strauss labeled "the first storms of revolution" didnot subside, yet the composer persevered in his public service to the regimethrough 1934 and into 1935, never joining the Nazi Party nor adapting to itstotalitarian tactics, yet also never publicly distancing himself from itspolicies or relinquishing his prominent post. At the same time, he declined toembrace Nazi-style race hatred, drawing the ire of Nazi cultural bureaucrats byrefusing to sign decrees that would expel Jewish members of the Reich Chamberof Music. And most scandalously of all, he attempted to secretly continue hiscollaboration with Zweig.

Withboth men having worked with remarkable speed, Die schweigsame Frau wascompleted by the fall of 1934. Looking back, Strauss later recalled,"Except for a minor cut in Act II ... I was able to set [Zweig's libretto]to music lock, stock, and barrel, without the slightest further change. None ofmy earlier operas was so easy to compose, or gave me such light-heartedpleasure." And so Strauss, eager to sustain momentum with his newlibrettist, sought to simply forge ahead and commence a second operatic projectwith Zweig. Eminently practical, the composer simply proposed what must haveseemed to him like a perfectly logical work-around: Zweig should continuewriting for him in secret, producing librettos for operas that would simply"go into a safe that will be opened only when we both consider the timepropitious."

Zweig howeverhad grown privately appalled and embarrassed by Strauss's partnership ofopportunity with the Nazi regime. He seems to have never seriously consideredacceding to Strauss's offer of writing for the safe, yet in demurring, he usedthe notion of an embarrassed veil of secrecy to nudge Strauss, ever sotactfully, toward a clearer recognition of the actual situation, all under theguise of flattery and without addressing the matter directly."Sometimes," Zweig wrote,

I have the feeling that you are not quite aware-andthis honors you-of the historical greatness of your position, that you thinktoo modestly about yourself Everything you do is destined to be of historicalsignificance. One day, your letters, your decisions, will belong to allmankind, like those of Wagner and Brahms. For this reason it seemsinappropriate to me that something in your life, in your art, should be done insecrecy. ... A Richard Strauss is privileged to take in public what is hisright; he must not seek refuge in secrecy, No one should ever be able to saythat you have shirked your responsibility.

This last line in particular was an admirable attempt, but it seems ultimately tohave only frustrated Strauss, who grew increasingly insistent and evenpetulant, by turns pleading with and haranguing his librettist. On February 26,1935, Strauss couched his request in the language of steadfastness, writing toZweig,

"I will not give up on you just because we happento have an anti-Semitic government now." On April 13,1935, there was a tone of self-pity: "[Your letter) saddens me becauseI sense in it your discouragement about our 'time,' which is apt to disturbconsiderably our working together... Please stay with me.... The rest will takecare of itself. On May 24, 1935, Strauss tried implying selfishness onZweig's part: "Please give my artistic needs some thought."And on June 22, 1935, he tried appealing to Zweig's high artistic principles:"If you could see and hear how good our work is, you would drop all raceworries and political misgivings with which you, incomprehensibly to me,unnecessarily weigh down your artist's mind, and you would write as much aspossible for me." Whatever rationalizations Strauss had deployed tojustify, if only to himself, his continued service to the regime and hisongoing attempts at flattering senior Nazi officials (which included, duringthis same period of pressuring his librettist, the gifting of the manuscriptscore of his opera Arabella as a wedding present to Hermann Göring), Zweig sawclearly that none of this could end well for either of them. By that point, theauthor's own books had been burned in cities across Germany. The final decisivemoment came in February 1934, when police turned up at Zweig's home demandingentry to search for "hidden arms." Zweig saw the intrusion for whatit was a targeted act of harassment, a violation of his freedom, a "moralslap in the face," and an omen of things to come. Immediately thereafter,he began the complicated process of disentangling his affairs, dismantling hisvast collections, selling his home, and setting up a new life for himself inLondon.

Nevertheless,even after having taken such decisive action, Zweig could not break the spellof Strauss's own self-delusion. In a letter to the theater historian JosephGregor (who would later take over as Strauss' librettist), Zweig complained,"I only wish (Strauss) would find the energy to throw in the towel afterthese experiences and comprehend who he is in comparison to all of them."And later again to Gregor: "The tragedy of the whole thing is that Straussrefuses to comprehend in spite of my unyielding repetitiousness that I do notwant to continue working with him. He is unable to accept that because of hispublic actions I refuse every public connection with him, in spite of how muchI admire him personally." Perhaps Zweig finally gave more explicit voiceto these sentiments when he wrote to Strauss directly on June 15, 1935, but wewill never know. That fateful letter has rather suspiciously not survived; thecomposer, it has been speculated, may have destroyed it in a fit of rage.Whatever Zweig wrote that day, it elicited a veritable tirade from Strauss. Thecomposer's reply of June 17, 1935, to Zweig's now-missing letter is worthquoting at length, both for Strauss's own words and for the ripple effect thisletter would subsequently have on Strauss's musical-political career in theNazi state. Strauss wrote,

Your letter of the 15th is driving me to distraction!This Jewish obstinacy! Enough to make an anti-Semite of a man! This pride ofrace, this feeling of solidarity! Do you believe that I am ever, in any of myactions, guided by the thought that I am "German" (perhaps, qui lesait)? Do you believe that Mozart composed as an "Aryan"? I know onlytwo types of people: those with and those without talent. The people [das Volk]exist for me only at the moment they become audience. Whether they are Chinese,Bavarians, New Zealanders, or Berliners leave me cold. What matters is thatthey pay full price for admission. ... So I urgently ask you again to work outthose two one-act plays as soon as possible.... Who told you that I exposedmyself politically? Because I have conducted a concert in place of thatobsequious, lousy scoundrel Bruno Walter? That I did for the orchestra's sake.Because I substituted for Toscanini? That I did for the sake of Bayreuth. Thathas nothing to do with politics. It is none of my business how the boulevardpress interprets what I do, and it should not concern you either. Because I apethe president of the Reich Music Chamber? That I only do for good purposes andto prevent greater disasters! I would have accepted this troublesome honoraryoffice under any government, but neither Kaiser Wilhelm nor Herr Rathenauoffered it to me. So be a good boy, forget Moses and the other apostles for afew weeks, and work on your two one-act plays.

Somuch about this extraordinary letter reflects the blinding force of artisticegoism. One may deduce from the composer's indignation that in Zweig's priorletter the writer had expressed some sense of solidarity with Jewish Germans asa persecuted minority. But rather remarkably, this sentiment now promptsStrauss to accuse Zweig of Nazi-style (Wagnerian) racial essentializing: CouldZweig actually be foolish enough to believe that Mozart composed as an"Aryan," and Strauss as a "German"? Strauss seems strangelyincapable of grasping the simple fact that Zweig did not have a choice as towhether he would assert his own Jewish identity at this moment in history; itwas being thrust upon him with brutal force by the very government Strauss wasactively serving.

We will never know how Zweig responded to Strauss's letter, because he neverreceived it. Strauss had for months been under surveillance by the Gestapo,which had also been opening his mail. The text of the letter was forwardeddirectly to Hitler, setting in motion a decisive chain of events. The composerwas summoned to Nazi headquarters in Berchtesgaden and forced to resignimmediately from the Reich Music Chamber under the public pretext of poorhealth. Indeed, it is impossible to know how much longer the composer wouldotherwise have maintained his official position in the Nazi regime, especiallygiven how assiduously he attempted to salvage his post after this debacle. Hisefforts included penning a groveling letter to Hitler, seeking a private audienceand a chance "to justify my actions to you personally." Hitler neverreplied. As one German scholar has persuasively argued, Zweig's "Jewishobstinacy" ultimately saved Strauss from further damaging his own legacy.

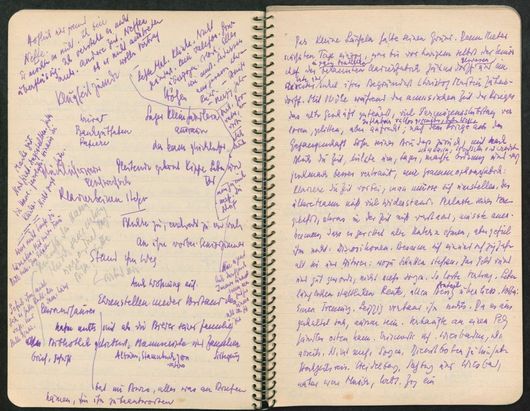

Writingprivately in his notebook, Strauss later reflected on the incident with adegree of introspection and regret:

Now I might examine the price I had to pay for notkeeping away, from the beginning, from the National Socialist movement. It allstarted when, to do a favor to the Philharmonic Orchestra... I substituted inthe last subscription concert for Bruno Walter who had been driven out. Thehonorarium of 1,500 marks I gave to the orchestra. That started a storm againstme by the foreign and especially the Jewish Viennese press, which did moredamage to me in the eyes of all decent people than the German government canever compensate me for. I was slandered as a servile, selfish anti-Semite,whereas in truth I have always stressed at every opportunity to all the peoplethat count here (much to my disadvantage) that I consider the [Nazi publisherand propagandist Julius Streicher-Goebbels Jew baiting as a disgrace to Germanhonor, as evidence of incompetence, the basest weapon of untalented, lazymediocrity against a higher intelligence and greater talent. I openly testifyhere that I have received so much support, so much self-sacrificing friendship,so much generous help and intellectual inspiration from Jews that it would be acrime not to acknowledge it all with gratitude.

Asfor Die schweigsame Frau, even before Strauss's letter had been intercepted,the opera faced an uncertain fate-could a work co-created by Germany's mostrevered living composer and a Jewish librettist actually be premiered in a Nazistate? Eventually, with Hitler's personal permission, granted before Strauss'sfateful letter, a premiere was scheduled to take place at the DresdenStaatsoper on June 24, 1935. To his credit, Strauss suspected Nazi chicanerybehind the scenes, and two days before the premiere he demanded to see theprogram, only to note that Zweig's name had been omitted. Strauss insisted itbe restored or else he himself would boycott the premiere, and ratherremarkably, he prevailed. Even though the librettist himself would not risk thetrip to Germany to attend the premiere in person, Zweig's name did appear onthe program, and its inclusion had its own ripple effects: Hitler canceled hisplans to attend the premiere, and Goebbels's flight to Dresden was called backin midair.

Theperformance nonetheless went forward, with Strauss pronouncing it a "greatsuccess." Katharina Kippenberg, the wife of Zweigs publisher, dashed off aletter to Zweig in Zurich, describing the event in terms that suggest a kind ofbreathless desire for continuity, however fleeting, with the rites andresplendence of an earlier era:

The house was completely sold out-it was a veryglamorous gathering, the ladies had made a real effort to look their prettiestand most elegant.... The atmosphere was very festive. It put me in mind of DerRosenkavalier-how many years, or rather decades, ago was that? ... Dieschweigsame Frau was a complete triumph all round, and that is certainly duenot least to the libretto, which is delightful, and of which Richard Strausshas said that nothing so good has been written since Figaro, calling it themost workable text he has ever been given.

Thecomposer's enthusiasm for Zweig's libretto was apparently not shared by theGerman press, which did not mention Zweig's name in reviews. After threeperformances in Dresden, the opera was banned for the remaining years of theThird Reich.

MOST OF ALL, HIGHLY RECOMMEND <TIMES’S ECHO> by JEREMY EICHLER. THE STORY ABOUT RICHARD STRAUSS AND STEFEN ZWEIG IS MAINLY FROMTHIS BOOK, WITH MINOR EDITED.