1917: La Chansonde Craonne

Whenever the accordion plays the melody of LaChanson de Craonne, I feel as if I’m touching the damp earth of the Frenchtrenches in the spring of 1917. This is not a work meticulously crafted by acomposer in a quiet studio; it is a testament to survival, written by countlessfrostbitten hands.

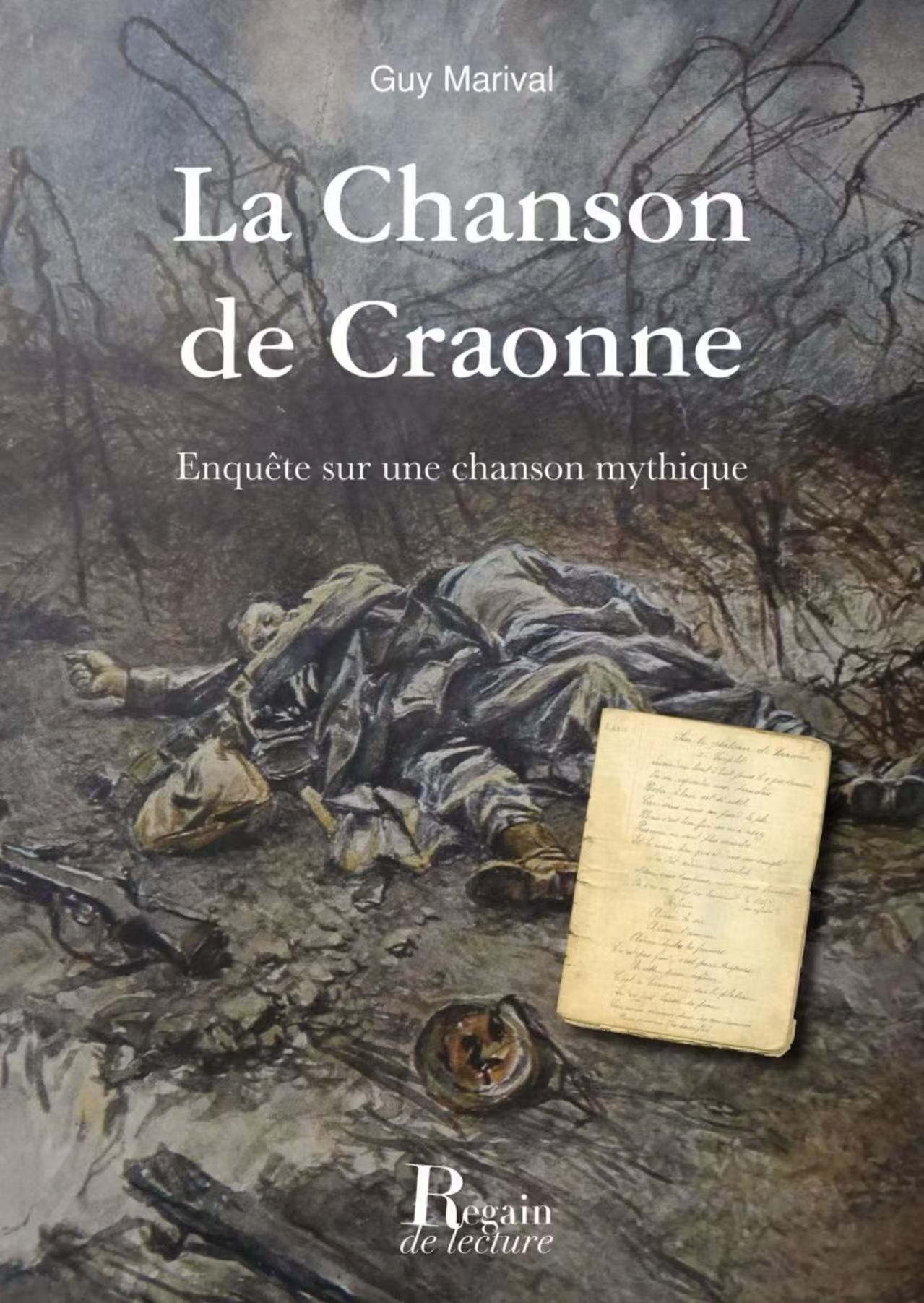

In 1917, France was mired in the quagmire ofwar. The blood of Verdun had not yet dried, and General Nivelle’s insistence onlaunching a new offensive filled the trenches with the scent of death. It wasduring the Second Battle of the Aisne that Craonne—a tiny, insignificant dot onthe map—became the terminus for innumerable young lives. Soldiers etched themelody onto their ration boxes with bayonets and plucked out the tune onbattered accordions smeared with mud. Every note carried their mockery of generals,their contempt for politicians at home, and their longing for the vineyards oftheir childhood—woven into a song destined to be forbidden.

Legend has it that on a rainy April evening,three infantrymen from Burgundy revised the lyrics in an air raid shelter.Using the lead from captured German pencils, they scribbled on cigarettepapers. Each time they wrote, “As we say goodbye to the girls in Longreaux,”someone would fall silent—some of them were indeed from that wine-producingtown. As the handwritten sheets circulated secretly through the trenches,soldiers would spontaneously fill in missing lines, like depositing fragmentsinto a communal memory jar. Rumor held that on the eve of an assault, theentire company quietly sang the forbidden song, the sound vibrating across thebarbed wire and startling flocks of crows.

When this song, born of despair, finallyreached Paris, it caused a storm in the underground taverns of theworking-class districts. Authorities were horrified to discover that the verysoldiers they called “cannon fodder” had woven a banner of resistance out ofmusical notation. One night in 1918, a printing apprentice risked his life toslip the lyrics into Le Figaro, and the next day, the muted hum of the songreverberated through the Paris Métro like molten lava stirring beneath thecity.

The first time I heard Yves Montand interpretthis song with his gravelly voice, I realized that art’s sharpest edge is not afinely honed dagger, but this rough, instinct-forged knife of survival.“Farewell to life, farewell to love”—these simple words cut deeper than anyornate rhetoric. When Montand lowered his eyelids to sing the final note at his1962 concert, it felt as if the theater’s dome floated above seventy thousandbodies who would never return home, their uniform pockets still holding fadedphotographs of their beloveds.

This requiem, grown from graves, continues toconfront the powers of every era: when you speak grandly of national glory,have you ever heard the faint clicks of the last five bullets counted in atrench? Perhaps the truest power of art lies in the crude, frozen-fingerednotes scrawled by an unknown soldier.